Teresa Sowińska: Mija właśnie 60 lat od otwarcia przy Staromiejskim Domu Kultury w Warszawie Galerii Krzywe Koło, powstałej z inicjatywy Mariana Bogusza w połowie 1956 roku na fali „odwilży”. Galerię tę od początku uznano – w kontekście ówczesnej rzeczywistości politycznej – za zjawisko bezprecedensowe po naszej stronie żelaznej kurtyny. Ty także wpisałaś się w historię Galerii jako jej kurator w latach 1974-1979. Spotykamy się, żeby porozmawiać o Twoich związkach z Krzywym Kołem i o Galerii, która czasowo stała się Twoją.

Teresa Panasiuk: To za wiele powiedziane, że wpisałam się w historię Galerii Krzywe Koło. Pod tą nazwą występowała za czasów Bogusza, do 1965 roku, później została przemianowana na Galerię Sztuki Współczesnej i taką oficjalną nazwę nosiła w okresie, gdy ja kierowałam jej działalnością. Jednak pierwotna nazwa, zakorzeniona w powszechnym obiegu, rzeczywiście utrzymywała się przez długie lata. Myślę, że to przywiązanie do nazwy, żywe nawet w pokoleniu, które Krzywego Koła nie znało z autopsji, świadczyło o należytej ocenie roli i znaczenia formacji związanej z Galerią, formacji, która zainicjowała ciąg manifestacji artystycznych, prowadzących do przełomowych zmian w sztuce.

T.S.: Należysz do pokolenia, które akurat w momencie zaistnienia Galerii Krzywe Koło, tym okresie „Sturm und Drang”, zaczynało wchodzić w dorosłość. Jak młodzi ludzie, zainteresowani sztuką czy już ją studiujący, reagowali na dochodzące stamtąd rewelacje? Czy je w ogóle zauważali?

Teresa Sowińska: 60 years have just passed from the opening of the Bent Circle Gallery at the Warsaw Old Town Culture Center that was founded on the initiative of Marian Bogusz in the middle of 1956 on a roll of the “thaw”. From the very beginning the Gallery has been considered – within the context of the then political realities – an unprecedented phenomenon on our side of the iron curtain. You have also left your imprint on the Gallery history as its curator in the years 1974-1979. We are meeting today to talk about your ties with the Bent Circle and the Gallery that for the time being was yours.

Teresa Panasiuk: This is too much to say that I left my imprint on the Bent Circle Gallery history. It had carried this name in the times of Bogusz, till 1965; later it was renamed as the Contemporary Art Gallery, and that is how it was officially called in the period when I was managing the Gallery. Nevertheless, the original name, deeply rooted in universal awareness, had functioned for many years. I believe that the attachment to the name, deeply rooted in the awareness of the generation who had not known the Bent Circle from personal experience, is an evidence of a correct assessment of the role and significance of the group related with the Gallery, the group that had initiated a chain of artistic manifestations that brought about the breakthrough transformations in art.

T.S.: You are a representative of the generation who was maturing in the period of “Sturm und Drang” when the Bent Circle Gallery came into being. How did young people interested in art and art students react to these changes? Did they notice

T.P.: Tego nie dawało się przegapić! Z oczywistych powodów Krzywe Koło było miejscem nie do ominięcia, ważnym, tam się po prostu chodziło. Przede wszystkim na wystawy. Inne niż gdziekolwiek. Te wystawy (i atmosfera im towarzysząca) potwierdzały, że przynajmniej w sferze duchowej i kulturowej wciąż pozostajemy w Europie. Dla nas, studentów Akademii, miały walor poznawczy, stymulowały proces dojrzewania artystycznego i intelektualnego, inspirowały niezależność myślenia. Galeria przyciągała jak zakazany owoc, z racji o charakterze artystyczno-politycznym. To nie była tylko placówka wystawiennicza, to coś więcej. Pamiętam, jaką sensację i dreszcz emocji wywoływała upiorna, niesamowita aranżacja zlokalizowanej w piwnicy Sali klubu jazzowego, gdzie wmontowano w ścianę stanowiącą tło dla estrady zgniecioną, rozmiażdżoną maskę citroena – czytelny wówczas dla każdego symbol bezpieki…

T.S.: … na kilkadziesiąt lat przed zapanowaniem masowej mody na sztukę instalacji, z domieszką pop-artu. Kto był autorem tego prekursorskiego obiektu i co się z nim stało?

T.P.: Nie mam pewności co do autorstwa, może Bogusz, może Bronisław Kierzkowski, trudno rozstrzygnąć. Tkwiło to monstrum w ścianie przez lata. Przy remoncie, już po moim odejściu z Galerii, zostało skute, tyle wiem. Pewno wylądowało w składnicy złomu.

T.S.: W 1965 roku, po odejściu Bogusza, Galerii groziła likwidacja, ponieważ pokazywana tam sztuka abstrakcyjna demoralizowała (sic!) radzieckie wycieczki zwiedzające Starówkę. To nie anegdota, lecz oficjalny argument władzy, a konkretnie – towarzysza sekretarza KW PZPR (dla młodego czytelnika należy rozszyfrować ten skrót: Komitet Warszawski Polskiej Zjednoczonej Partii Robotniczej), niejakiego Kępy Józefa. Ostatecznie skończyło się na pogróżkach. Prowadzenie Galerii objął Juliusz Narzyński. Czy było to dobre rozwiązanie?

them at all?

T.P.: This was impossible to overlook! For obvious reasons the Bent Circle was an important spot not to be missed; the very place to visit. First of all, to watch exhibitions. Different than anywhere else. These exhibitions (and their climate) proved that – at least in the spiritual and cultural area – we still belonged to Europe. For students of the Academy, they carried a cognitive factor, stimulated the process of creative and intellectual maturity, inspired an independent way of thinking. The Gallery attracted, like a forbidden fruit, for artistic and political reasons. This was not only an exhibition space but something much more.

I remember a sensation and a shiver of emotion caused by a ghastly, extraordinary arrangement located in the basement room of the jazz club, where a crushed and scrunched Citroen hood – an obvious for all symbol of security services - was fixed into the wall being a background for the stage…

T.S.: …a couple of dozen years before installations with an element of pop-art became a mass trend. Who was the author of this forerunning object, and what has happened to it?

T.P.: I am not sure about the author. Perhaps Bogusz, perhaps Kierzkowski, it is hard to tell.

The monster stuck into the wall remained there for years. During the refurbishment when I left the Gallery it was hammered down, this is all I know. Quite likely, it ended on a scrap heap.

T.P.: In 1965, after Bogusz left, the Gallery was about to be closed down, since the abstract art presented there demoralized (sic!) Soviet package tours sightseeing the Old Town. This is not an anecdote but an official argument used by the regime, to be more exact, by comrade secretary of the Warsaw Committee of the Communist Party ( KW PZPR) (for young readers, the abbreviation stands for the Warsaw Committee of the Polish United Workers

Potwierdzenia udziału artystów w salonie letnim, 1975

Confirmation of the artists participation in the summer salon, 1975

<

>

T.P.: Innego nie było. Najważniejsze, że udało się zachować to miejsce dla sztuki, Warszawie brakowało lokali wystawowych. Narzyński był znakomitym kandydatem na szefa Galerii i sprawdził się w działaniu. Doceniając potrzebę zachowania ciągłości, przejął dotychczasowy model funkcjonowania, kładąc akcent na sztuce aktualnej i prezentacji młodego pokolenia. Zależało mu na tym, by Galeria, mimo zmiany nazwy, była postrzegana jako kontynuacja Krzywego Koła.

T.S.: Rzeczywiście tak było; często pojawiały się tam indywidualne wystawy młodych artystów, których się znało z najróżniejszych wystaw zbiorowych, ogólnopolskich, poplenerowych. Mimo że na tych zbiorówkach wyróżniali się na tle całości, długo musieliby czekać na pokaz indywidualny w galeriach bardziej „oficjalnych”. Znasz to zresztą z własnego doświadczenia.

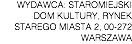

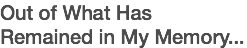

T.P.: Wywołałaś temat, niezręcznie mi o tym mówić, by nie wyjść na megalomankę, ale zaryzykuję: moja pierwsza, „poważna” wystawa indywidualna też odbyła się w Galerii za czasów Narzyńskiego; wcześniej miałam wprawdzie kameralny pokaz w Domu Kultury w Kołobrzegu, ale działo się to jakby na peryferiach życia artystycznego, choć mile wspominam ten pierwszy kontakt z widzem. Wystawa w Galerii Sztuki Współczesnej to było dla mnie coś w rodzaju nobilitacji. Który to był rok? Pewno pamiętasz, bo napisałaś mi wstęp do katalogu.

T.S.: Rok był 1970, dla mnie pamiętna data, ponieważ był to mój pierwszy tekst, jaki ukazał się drukiem. Zasługa to dr Bożeny Kowalskiej, mojej szefowej z „Zachęty”, gdzie pracowałam. Było chyba tak, że z braku czasu nie mogła sama napisać, więc zaproponowała mnie w zastępstwie i jakoś nas skontaktowała. Wtedy jeszcze się nie znałyśmy. O Twoim malarstwie miałam wyobrażenie dość mgliste, ale na podstawie zapamiętanych obrazów z wystaw zbiorowych w Zachęcie i Domu Plastyka kojarzyło mi się dobrze. Gdy znalazłam się w Twojej pracowni przy Żurawiej, by obejrzeć prace, i dotarło do mnie, że wystawa odbędzie się w Krzywym Kole, wpadłam w panikę. Próbowałam cię przekonać, że nie jestem właściwą osobą, że powinien napisać to ktoś z nazwiskiem, a nie nowicjusz, w dodatku jeszcze bez dyplomu ukończenia studiów. Zbagatelizowałaś moje skrupuły lakonicznie…

Party), someone called Kępa Józef. Finally, it ended with a warning. Juliusz Narzyński took over the Gallery management. Has this been a good solution?

T.P.: The only one possible. The spot was saved for art, and this was essential. Warsaw lacked exhibition space. Narzyński was an excellent candidate to head the Gallery, and he performed very well. Being aware of the need to preserve continuity, he followed the so far model of functioning, with the focus on contemporary and young generation art presentation. It was his aim that the Gallery, in spite of the change of its name, was perceived as the continuation of the Bent Circle.

T.S.: Indeed this was the reality; they frequently showed one-man exhibitions by young artists who were known from various collective, all-Poland or post plein-air workshops presentations. In spite of the fact that during collective events they stood out against the average background, they would have had to wait for a long time to mount a one-man exhibition at one of the more “official” galleries. Anyway, you know this from your own experience.

T.P.: You brought back the topic. I feel awkward to talk about this so as not to sound like a megalomaniac, but I will take the risk: my first “serious” one-man exhibition was put up at the Gallery under Narzyński. To be honest, earlier I had a small exhibition at the Culture Center in Kołobrzeg, though it took place, so to speak, on the fringes of the artistic life, nevertheless I have pleasant memories of my first contact with the audience. The exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery was a sort of great honor for me. Which year was it? You are likely to remember since you wrote an introductory word for my catalogue.

T.S.: This was 1970. A memorable date for me because it was my first text to appear in print. I owe this to Bożena Kowalska, PhD, my boss from the „Zachęta” where I had worked then.

I think that she was too busy to write it herself, so she suggested me as a replacement, and she somehow got us in touch. I had not met you earlier, and I had got merely a hazy notion of your painting, though - based on the pictures I remembered from collective exhibitions held at the Zachęta and in the Artist’s

Potwierdzenia udziału artystów w salonie letnim, 1975

Confirmation of the artists participation in the summer salon, 1975

<

>

T.P.: Tak, przypominam to sobie; miałaś kajecik i robiłaś notatki. To mnie dowartościowało: oto ktoś ogląda moje obrazy, słucha, co mam do powiedzenia o sztuce, trafnie odczytuje moje intencje, nie popisuje się, aż tu nagle ulega panice. Pamiętam, że powiedziałam „no i bardzo dobrze, będą dwa debiuty”. I były.

T.S.: Przekonałaś mnie wtedy, wróćmy jednak do tematu Galerii. Lata mijają, jest rok 1974. Jesteś młodą malarką z wyraziście zarysowaną drogą poszukiwań, masz na swoim koncie wspomnianą wystawę indywidualną, udział w wielu wystawach zbiorowych, w plenerach, ponadto cztery lata pracy (1964-1968) na stanowisku asystenta w pracowni Jana Wodyńskiego na Wydziale Malarstwa ASP w Warszawie. Co wpłynęło na Twoją decyzję, by poświęcić parę lat życia na prowadzenie Galerii?

T.P.: Otrzymałam tę propozycję od Julka Narzyńskiego. Była dla mnie atrakcyjna, pociągająca, dawała możliwość zmierzenia się z czymś dla mnie nowym, nieznanym. Na podjęcie decyzji potrzebowałam trochę czasu. To była trudna decyzja.

T.S.: Dlaczego?

T.P.: Nie miałam pewności, czy dam sobie radę. Ranga Galerii wciąż onieśmielała i zobowiązywała. Musiałam gruntownie rozważyć, czy potrafię utrzymać standardy, które decydowały o jej pozycji i znaczeniu, ocenić, czy nie kierują mną wygórowane ambicje.

T.S.: Czy konsultowałaś się z Boguszem i czy jego zdanie miało wpływ na Twoją decyzję?

House (Dom Plastyka) – it carried positive associations. When I visited your atelier in

Żurawia Street to see your pieces, and when I realized that the exhibition was to be showed at the Bent Circle, I got panic stricken. I tried to convince you that I was not the right person for the job, that it should have been written by someone with a well known name, not a novice, on top of that, one who has not received yet her studies graduation diploma. You ignored my objections laconically …

T.P.: Yes, I do remember; you carried a small notebook and you were taking notes. It boosted my ego: there is someone watching my pictures, listening to what I have to say about art, accurately interpreting my intentions, not showing off, and finally panicking. I remember what I said: “ this is great, there will be two debuts”. And there were.

T.S.: You convinced me then but let us come back to the topic of the Gallery. Time is passing, this is 1974. You are a young painter with a clearly outlined path of your creative quest.

You can boast the already mentioned one-man exhibition, participation in a number of collective shows and plein-air workshops, and over four years period (1964-1968) as a junior lecturer at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts Painting Department Jan Wodyński Faculty. What made you decide to devote a couple of years to run the Gallery?

T.P.: I got an offer from Julek Narzyński. It was quite attractive for me since it provided an opportunity to face a new challenge. I needed some time to take up a decision. It was a hard decision.

.jpg?crc=3983502837)

T.P.: Nie mogło być inaczej! Z Boguszem zawsze miałam dobre relacje, mimo że nasze poglądy i artystyczne wybory niekoniecznie były zbieżne. Dla mnie było ważne poznać jego zdanie, przecież Galeria Krzywe Koło to jego własność intelektualna i miał do niej niewygasłe prawa autorskie. Bogusz aprobował moją kandydaturę za pomocą zwykłej swojej formułki „masz myślenie”, co w jego języku znaczyło „nadajesz się”. Chyba właśnie jego stanowisko pozwalało mi z czystym sumieniem przejąć Galerię. Narzyński również uważał, że mam predyspozycje i wystarczające kompetencje, by prowadzić Galerię we właściwym kierunku.

T.S.: Post factum podzielam opinię Twoich starszych kolegów. Czy może przedstawiłaś im jakiś nowy, własny program, który chciałabyś realizować?

T.P.: Żadne z nas nie widziało potrzeby wprowadzania rewolucyjnych zmian, wprost przeciwnie – chodziło o kontynuację. Moim credo była kontynuacja, wynikająca z pietyzmu dla miejsca i ludzi, którzy to miejsce stworzyli. W Krzywym Kole program wystaw miał charakter pluralistyczny. Należało zachować tę różnorodność. To była sprawdzona formuła, dobrze służyła sztuce, artystom i widzowi. Chciałam, żeby Galeria pozostała miejscem przyciągającym publiczność, bo taki jest cel jej istnienia.

T.S.: Podejmujesz decyzję i w 1974 roku rozpoczynasz pracę w Galerii. Ma ona za sobą już osiemnaście lat istnienia, a Boguszowa batalia o sztukę nowoczesną wydaje się, z perspektywy czasu, odległym zjawiskiem historycznym. Ta wygrana w zawrotnym tempie batalia radykalnie odmieniła całokształt życia artystycznego w Polsce. Pozostały różne anomalie, jak cenzura czy mające charakter polityczny zakulisowa praktyki sterowania środowiskiem za pomocą takich narzędzi, jak zakupy muzealne, stypendia, prestiżowe wystawy zagraniczne, manipulacje medialne. Nie przesłania to jednak faktu, że postulat swobody wypowiedzi został zrealizowany. Sztuka rozwija się wielokierunkowo, reaguje na impulsy płynące z Zachodu, co poszerza jej środki wyrazowe, lecz niejednokrotnie wywołuje owczy pęd powierzchownego naśladownictwa, a w rezultacie rodzi banał, brak autentyzmu, nijakość. Nie chcę deprecjonować sztuki lat 70., miała cienie i blaski, i rozchwiane kryteria. Jak w takiej sytuacji dokonywać trafnych wyborów przy konkretyzowaniu programu wystaw?

T.S.: Why?

T.P.: I was not sure if I would cope. The status of the Gallery still intimidated me, and the task was quite demanding. I had to consider, whether I would be able to keep the standards that had determined its position and significance; and to judge, if this was not too high for my boots.

T.S.: Have you consulted Bogusz, and has his opinion influenced your decision?

T.P.: It could not have been otherwise! I have always had good relations with Bogusz, even though our points of view and artistic choices have not necessarily coincided. It was important for me to know his opinion since the Bent Circle Gallery has been his intellectual property and his copyrights to it has not expired. Bogusz supported my candidacy, by means of his usual comment “you’ve got thinking” which in his language meant “you are fir for it”. This was his position that let me take over the Gallery with a clear conscience. Further, Narzyński also believed that I was predisposed, and that I had sufficient competences to run the Gallery in the right direction.

T.S.: Post factum, I share opinions of your older colleagues. Did you suggest to them your own program that you would like to implement?

T.P.: None of us saw the need to introduce any revolutionary changes, on the contrary – we all were for the continuation. The continuation was my creed, resulting from the deep reverence for the location and the people who had founded this place. The Bent Circle exhibition program was of the plural nature. It was vital to preserve this variety. This was a proven formula that had been serving well art, artists and viewers. I wished the Gallery remained the spot that attracted audiences; this was the objective of its existence.

T.S.: You took up the decision, and in 1974 you started working at the Gallery. The Gallery had been in existence for eighteen years, and the struggle for modern art, initiated by Bogusz, seems a distant historical phenomenon, when looked at from the time perspective. This battle, won with a dizzying speed, has drastically changed the overall shape of the artistic life in Poland. Various anomalies have remained, such as censorship or politically driven backstage practices to control artists by means of such tools as museum purchases, grants, prestigious foreign

T.P.: Zdawałam sobie sprawę, że atrakcyjny plan wystaw to podstawa sukcesu. Paradoksalnie, pod tym względem Bogusz miał sytuację bardziej komfortową, szczególnie w pierwszych latach po zaistnieniu Galerii. Nie tylko dlatego, że był supermistrzem organizacji i improwizacji. Po prostu, grono artystów, którzy spełniali jego kryteria nowoczesności, było na tyle wąskie, że prawie nie istniał problem wyboru. Ponadto, byli to artyści głodni wystaw, wielu miało przerwę w wystawianiu od 1948 roku, bo albo ich nie dopuszczano – jako formalistów, albo sami stosowali bojkot oficjalnych wystaw, więc niemal wszystko, co zawiesili na ścianach Galerii, budziło zainteresowanie. W latach 70. skala propozycji artystycznych jest znacznie rozleglejsza. W warunkach embarras de richesse budowanie programu wystaw w Galerii wymaga wysiłku i dobrej orientacji. Łatwiej dokonać wyboru, czegokolwiek by dotyczył, gdy oferta składa się z dwu obiektów, znacznie trudniej, gdy wybrać trzeba jeden z dwudziestu. Ale wybieranie jest wpisane w proces twórczy, to składnik mojej codziennej pracy. Malując obraz, cały czas dokonuję określonych wyborów, które podpowiada mi intuicja, podświadomość i wiedza malarska. Przy wyborze czy doborze wystaw trzeba tylko zmienić kolejność, na pierwszym miejscu stawiając wiedzę. Uważałam, że mam dosyć dobre rozeznanie odnośnie do aktualnych zjawisk w sztuce dzięki nawykowi oglądania wystaw, dzięki plenerom i kontaktom z kolegami po fachu. Czteroletniej pracy w ASP zawdzięczałam znajomości z artystami z różnych pokoleń, możliwość wymiany myśli, poznawania ich twórczości. Wcześniej jeszcze moje rozumienie sztuki kształtowało się podczas studiów, w pracowni Artura Nachta-Samborskiego, który był znakomitym pedagogiem, a nawet więcej – był Mistrzem. Rekapitulując: tak widziałam swoje ewentualne atuty, pozwalające na prowadzenie Galerii. Oczywiście, nikt nie ma patentu na nieomylność, zawsze istnieje ryzyko błędu, jak w każdym ludzkim działaniu.

T.S.: Podkreślałaś potrzebę zachowania ciągłości w odniesieniu do założeń programowych Krzywego Koła. W jaki sposób Twoje credo przekłada się na działania konkretne, gdy już sama musisz zmierzyć się z tym problemem?

artists by means of such tools as museum purchases, grants, prestigious foreign exhibitions, media manipulation. All these, however, do not overshadow the fact that the postulate of the freedom of expression has been implemented. Art is developing multi directionally, sensitive to Western trends, thus the means of expression get expanded. This frequently leads to a flock of sheep type of behavior and to superficial imitations, which in turn result in banality, lack of the authentic, and mediocre works. This is not my intention do depreciate the art of the 70’s; it had its bright and dark aspects, and unstable criteria. How in this situation can one make an accurate choice with regard to exhibitions program?

T.P.: I was aware that an attractive exhibition plan translated into a success. Paradoxically, in relation to this, Bogusz had been in a more comfortable situation, particularly in the early period of the Gallery existence. Not only because he had proved excellent organizational and improvisation skills. Simply, a group of artists, who met his criteria of being modern, was narrow enough that he practically had not faced the dilemma of choice. Further, these had been artists keen on exhibiting, a number of them had not presented their works since 1948 – some had not been admitted, i.e., formalists; others had boycotted official exhibitions. Thus, practically everything that they put on the Gallery walls was interesting. In the 70’s, artistic offer is much wider. In the circumstances of the embarrass de richesse the Gallery exhibitions agenda requires an effort and good orientation. It is easier to make a selection, whatever it pertains to, when an offer covers two items, the task is much more difficult when one must pick up one out of twenty. Nevertheless, making choices has been inherently written into a creative process, being an element of my everyday work. While painting a picture, I am constantly selecting, guided by my intuition, the subconscious and painting knowledge. While working out exhibitions agenda, one has merely to change the order. Knowledge must come first. I think I have a quite good insight into current phenomena in art, owing to a habit of watching exhibitions, plein-air workshops and contacts with fellow artists. Due to four years work at the Academy of Fine Arts, I know numerous artists of various

T.P.: Myślę, że potrzeba ciągłości jest zakodowana w ludzkiej psychice. Zapadło mi w pamięć wiele wystaw z Krzywego Koła, których myślą przewodnią było ukazywanie różnorodności sztuki poprzez zderzanie indywidualności i języka ekspresji, konfrontowanie postaw, tendencji, pokoleń. W obrębie jednej wystawy spotykają się prace nestorów, jak Henryk Stażewski, Alfred Lenica – i prawie debiutantów, jak Tadeusz Dominik, Stefan Gierowski, Zbigniew Makowski, Rajmund Ziemski oraz pokolenia pośredniego, jak Marian Bogusz, Tadeusz Brzozowski, Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Nowosielski, Alina Szapocznikow, Jan Tarasin, Magdalena Więcek.

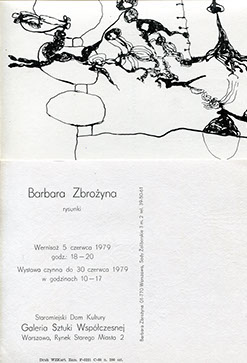

Tak odrębne światy składały się na zadziwiającą, spójną wewnętrznie i harmonijną całość. To było, bez przesady, coś na kształt minimuzeum sztuki nowoczesnej. Wzór inspirujący, jednak z różnych względów trudny do kontynuowania. Być może udało mi się osiągnąć zbliżony efekt, gdy na Salon Letni przygotowałam wystawę rzeźby, w której uczestniczyli Krystian Jarnuszkiewicz, Anna Kamieńska-Łapińska, Adolf Ryszka, Barbara Zbrożyna. W programie realizowanym przeze mnie ilościową przewagę miały wystawy indywidualne, dające możliwości startu debiutantom. Starałam się wyławiać talenty młode, ale także i nieco starsze, wcześniej niezauważone.

T.S.: Domyślam się, że Galeria pozostająca pod zarządem ZMS preferowała wystawy sztuki młodych, żeby zanęcić najmłodsze pokolenie i zbijać na tym kapitał polityczny. Czy narzucano ci jakieś wystawy?

generations, I have an opportunity to exchange opinions and get familiar with their oeuvre. Earlier, my artistic understanding was shaped during my studies at the faculty run by Artur Nacht-Samborski, who was a great pedagogue, more – he was a Master. To sum up, I believed that the above were my potential trump cards to run the Gallery. Certainly, nobody is infallible, and there is always a risk of a mistake, like in any other kind of human behavior.

T.S.: You stressed the need to continue the program guidelines of the Bent Circle. How was your creed translated into real actions, when you had to face this problem yourself?

T.P.: I think that the need for continuity is being encoded in human psyche. I kept in mind a number of exhibitions showed at the Bent Circle, where the leading motto was to illustrate variety in art by means of contrasting the individual and the language of expression; confronting stands, trends, generations. One exhibition presents pieces by doyens, such as Henryk Stażewski, Alfred Lenica, and mere debutants, like Tadeusz Dominik, Stefan Gierowski, Zbigniew Makowski, Rajmund Ziemski and the mid generation artists including Marian Bogusz, Tadeusz Brzozowski, Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Nowosielski, Alina Szapocznikow, Jan Tarasin, Magdalena Więcek.

These separate worlds composed a surprising, internally coherent and harmonious whole. It is no overstatement to say that this was a kind of contemporary art museum. An inspiring case,

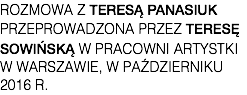

Maciej Szańkowski, pokaz "składników" na pl. Kanonia, Warszawa, 1975

Maciej szańkowski, the show in the kanonia square in warsaw, 1975

Wystawa Macieja SzańkowSkiego, "Rysunki Przestrzenne", 1979

The Exhibition by maciej Szańkowski, "Spatial Drawings", 1979

Wystawa Macieja SzańkowSkiego, "Rysunki Przestrzenne", 1979

The Exhibition by maciej Szańkowski, "Spatial Drawings", 1979

Maciej Szańkowski, pokaz "składników" na pl. Kanonia, Warszawa, 1975

Maciej szańkowski, the show in the kanonia square in warsaw, 1975

Maciej Szańkowski, pokaz "składników" na pl. Kanonia, Warszawa, 1975

Maciej szańkowski, the show in the kanonia square in warsaw, 1975

<

>

T.P.: Merytoryczna strona wystaw należała do mnie, niby miałam jakąś niezależność, ale pojawiały się kontrowersje i naciski. Wspomniany wcześniej Salon Letni z rzeźbą, naprawdę interesująca wystawa, z dużą frekwencją, zwierzchnictwo Galerii skwitowało krótko: „sami starcy!” Ci artyści byli w wieku około 40 lat, jedynie Zbrożyna była starsza. Koncepcja promowania sztuki młodych mieściła się w moim programie, byłam za, idąc śladem Krzywego Koła; jednocześnie uważałam, że nie można podchodzić do tego doktrynersko, opierając się wyłącznie na metryce. Wprowadziłam jednak do programu cykliczną wystawę, opartą na takim „metrykalnym” kryterium. Otóż zarzucono mi już na początku mojej pracy w Galerii, że nie świętuję 1 Maja, że nie przygotowałam w kalendarzu wystaw jakiegoś specjalnego pokazu pod hasłem w rodzaju „Niech się święci 1 Maja!”. Z kłopotliwej sytuacji wybrnęłam przy użyciu fortelu, z finalnym produktem z gatunku „dwa w jednym”, wprowadziłam mianowicie do planu wystaw doroczny Majowy Salon Młodych, na którym prezentowana była twórczość najmłodszych – dyplomantów i świeżo upieczonych absolwentów ASP. Młodzi ludzie byli szczęśliwi, że mają debiut w tak prestiżowym miejscu, ja również, bo udał się fortel, a przy okazji wykazałam się refleksem i inteligencją, Galerii przybyła interesująca wystawa, przyciągająca publiczność. Nie jestem pewna, czy moi decydenci byli w pełni usatysfakcjonowani, ale jakoś to przełknęli i nie wracali do tematu. Sztuka młodych była ponadto obecna na innej cyklicznej wystawie, jaką był Salon Letni, a zdecydowanie dominowała wśród wystaw indywidualnych i grupowych.

T.S.: Twój debiut w roli kuratora Galerii to wystawa malarstwa i rysunku Tomasza Ciecierskiego, wówczas „dobrze się zapowiadającego” trzydziestolatka; dziś należy on do najbardziej znanych malarzy polskich. Była to jego pierwsza wystawa indywidualna, jednocześnie wystawa otwierająca działalność Twojej Galerii. Czy ten wybór był dziełem przypadku, czy też może wyrażał jakieś przesłanie, deklarację?

T.P.: Jego prace pokazywane na wystawach zbiorowych zwróciły moją uwagę, był już kilka lat po dyplomie. Wydawało się, że jest wystarczająco dojrzały artystycznie, by przygotować wystawę indywidualną. Pewno chciałam zasygnalizować, że Galeria jest, tak jak zawsze była, otwarta na sztukę młodą, poszukującą.

T.S.: Ta otwartość, mająca za podstawę pluralizm estetyczny, pozwalała na prezentowanie szerokiego spektrum postaw i tendencji, jakie pojawiały się w sztuce aktualnej. Jako twórca miałaś jednak własny światopogląd, własną drogę i świat wartości. Można było pogodzić te sprzeczności?

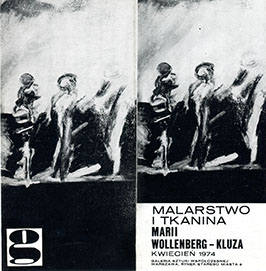

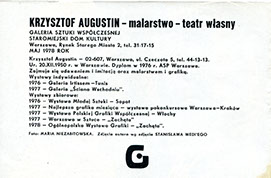

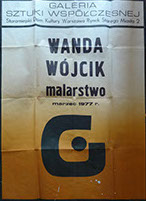

T.P.: Wystarczy nie być egocentrykiem, mieć dystans wobec własnych kryteriów. Nie chcę mówić o tolerancji, ponieważ dzisiaj to słowo ma kompletnie wypaczony sens. Wyważając proporcje między subiektywizmem a obiektywizmem, nie wchodziłam w konflikt z własnymi poglądami i sumieniem artystycznym, natomiast miałam szansę uchwycić i pokazać wielokształtność i różnorodność postaw artystycznych, nie ograniczać się do preferowania „jedynie słusznej” drogi. Nauczyłam się tego w Galerii. Nie wiem, czy udawało mi się osiągnąć zamierzony cel, ale takie miałam intencje. Wymienię, w porządku alfabetycznym, kilka nazwisk: Piotr Bogusławski, Zofia Broniek, Jerzy Budziszowski, Marian Czapla, Zofia Glazer, Adam Myjak, Grzegorz Pabel, Janusz Pastwa, Radwan Pąkowski, Bogumił Podstolski, Marek Sapetto, Anna Socha, Maciej Szańkowski, Wanda Wójcik… To zaledwie część spośród plejady młodych wówczas malarzy, grafików, rzeźbiarzy, którzy mieli indywidualne wystawy w mojej Galerii. W sztuce lat 70. byli to artyści, którzy określali kierunki poszukiwań młodej plastyki; wielu z nich ma dziś trwałe miejsce w dziejach polskiej sztuki, także z racji późniejszej pracy pedagogicznej w Akademii. Przyznaję, że nie wszyscy znaleźliby miejsce w moim prywatnym „muzeum wyobraźni”, natomiast w Galerii to miejsce im się należało. Galeria nie była dla mnie, była dla sztuki i publiczności.

T.S.: Często podkreślasz ten aspekt…

T.P.: …ponieważ Galeria nie powinna być pusta. Przecież nie urządza się wystawy po to, by zorganizować obrazom wycieczkę na bezludzie, lecz żeby pokazać je ludziom, którzy mają potrzebę je oglądać. Galeria musi być miejscem przyciągającym publiczność.

T.S.: Jaka była publiczność Twojej Galerii?

T.P.: Myślę, że taka jak wszędzie na wystawach, ludzie znani (z takich bardzo dziś znanych zapamiętałam Wisławę Szymborską) i nieznani, dużo młodzieży, wycieczki z okolicznych szkół, turyści, także zagraniczni, różnych nacji obcokrajowcy znający Bogusza i szukający z nim kontaktu, studenci i oczywiście artyści. Do stałych bywalców należeli studenci Wyższej Szkoły Oficerów Pożarnictwa z Żoliborza; budujący to był widok – grupa około pięćdziesięciu młodzieńców w mundurach, kultura w zachowaniu, zainteresowanie tym, co oglądają, sensowne uwagi. Wiernym i szczególnym widzem był rzeźbiarz Alfons Karny, który przychodził w godzinach porannych, by wypić kawę i ewentualnie dostać śniadanie.

T.S.: A czy Bogusz interesował się losem Galerii i recenzował Twoje wystawy?

T.P.: Bogusz był w tym czasie zaabsorbowany swoimi licznymi projektami monumentalnych realizacji przestrzennych; czasem były to pomysły graniczące z utopią. Na wernisaże raczej nie przychodził, ale wystawy oglądał i przy okazji spotkań ze mną mówił, że „wystawa jest w porządku”. Nie odnosiłam wrażenia, że to tylko formułka grzecznościowa, on nie był hipokrytą. Zarekomendował mi nawet zaprzyjaźnionego z nim niemieckiego grafika Elmara Flammera, z prośbą, by zrobić mu wystawę w Galerii. Oczywiście spełniłam tę prośbę, bo grafiki były interesujące, a ponadto miałam, bezkosztowo, kolejną wystawę sztuki zagranicznej, co wprowadzało jakieś urozmaicenie do programu.

T.S.: Czy zdarzało się, że korzystałaś z podobnych sugestii ze strony innych osób, które były dla Ciebie autorytetami?

An inspiring case, nevertheless,very hard to follow for various reasons. It is quite likely that I succeeded in achieving a similar effect with a sculpture exhibition prepared for the Summer Salon that featured pieces by Krystian Jarnuszkiewicz, Anna Kamieńska-Łapińska, Adolf Ryszka, Barbara Zbrożyna. The program I ran abounded in one-man exhibitions that provided an opportunity for a debut. I made an effort to fish out young talents, also slightly older, overlooked earlier.

T.S.: I guess that the Gallery supervised by Socialist Youth Movement (ZMS) encouraged young art exhibitions so as to attract the youngest generation and thus gain political benefits. Did they impose any exhibitions on you?

T.P.: Subject matter oriented aspects of exhibitions were my responsibility, I enjoyed some kind of independence, but there were controversial issues and pressure. The earlier mentioned Summer Salon, presenting sculpture, was a truly interesting exhibition, with good attendance, while the Gallery management commented shortly: “only old people!”. These artists were about 40 years, only Zbrożyna was older. The concept of promoting young art fitted well into my agenda; following in the footsteps of the Bent Circle, I was all for it. At the same time, I was of the opinion that one cannot approach it as a doctrine, based exclusively on a birth certificate. Nevertheless, my program covered a cyclical exhibition founded on the “Date of birth” criterion. From the very beginning of my work at the Gallery, I was accused of neglecting the May 1st. My exhibition plan was criticized because it lacked a special show “to celebrate the May 1st “. I solved the problem, resorting to a stratagem, resulting in a product of the “two in one” sort; I introduced into the exhibition program an annual May Salon of the Young that presented the work by the youngest - graduation year students and fresh graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts. Young people were very happy to have a debut in such a prestigious spot, so was I, since my stratagem succeeded. I showed my presence of mind and intelligence; the Gallery gained an interesting exhibition that attracted the audience. I am not sure, if decision makers were fully satisfied but they somehow swallowed it, and the topic never returned. Further, the young art was present on other cyclical show, namely the Summer Salon, and it dominated one-man and collective exhibitions.

T.S.: You debuted as the Gallery curator with the exhibition of painting and drawing by Tomasz Ciecierski, the then “promising” thirty-year-old; at present, one of the best known Polish painters. This was his first one-man exhibition, simultaneously, the exhibition that inaugurated your activity at the Gallery. Was it a haphazard choice, or did it carry a message or a statement?

T.P.: I noticed pieces by him presented on collective exhibitions. He graduated a couple of years earlier. He seemed artistically mature enough to prepare a one-man show. I think I wanted to give a clear signal that the Gallery - as it had always been – was still open to young and searching art.

T.S.: This openness, based on aesthetic pluralism, allowed for a presentation of a wide spectrum of points of view and tendencies that appeared in the current art. As an artist, however, you had your own outlook, own road and the set of values. Was it possible to reconcile these two contradictions?

T.P.: It is enough not to be egocentric, and to remain detached from one’s own criteria. I do not wish to talk about tolerance because today the term has got completely distorted sense. Weighing the proportions between the subjective and the objective, I was not in conflict with my points of view and artistic conscience, while I preserved an opportunity to grasp and show the multi shaped, various artistic stands, not being limited to prefer the “exclusively right” path. This is what I have learnt at the Gallery. I am not sure if I succeeded in gaining my goal, but these were my intentions. I will mention some names in an alphabetical order: Piotr Bogusławski, Zofia Broniek, Jerzy Budziszowski, Marian Czapla, Zofia Glazer, Adam Myjak, Grzegorz Pabel, Janusz Pastwa, Radwan Pąkowski, Bogumił Podstolski, Marek Sapetto, Anna Socha, Maciej Szańkowski, Wanda Wójcik… They are only a part of an array of the then young painters, graphic artists, sculptors, who put up one-man exhibitions at my Gallery. In the art of the 70’s, these were the artists who defined the directions of search of the young art; many of them have a permanent position today in the Polish art history, last but not least, due to their pedagogic effort at the Academy. I have to confess, however, that not all of them would have found a place in my private “museum of imagination”, while they deserved this place at the Gallery. The Gallery was not for me, it was to serve art and audiences.

T.S.: You have been quite frequently stressing this aspect…

T.P.: …because the Gallery should not be empty. It is not the exhibition organization purpose to take the pictures on the trip to a deserted island, but to present them to people who have the need to watch them. A gallery has to be the spot to attract audience.

T.S.: What was the audience of your Gallery like?

T.P.: I think like any other exhibition audience; well known people (out of the easily recognizable, I remember Wisława Szymborska) and the anonymous, a number of young people, tours from neighboring schools, tourists, including foreigners representing various nations, who met Bogusz and wanted to get in touch with him, students, and last but not least, artists. Among our regular frequenters, there were students of the Fire Cadets School from the Żoliborz district. It was a heartwarming view – a group of about fifty uniformed young guys; civilized conduct, an interest in what they were watching, intelligent comments. Alfons Karny, a sculptor, was a loyal and a very special visitor. He used to come in the early morning hours to have coffee, and an occasional breakfast.

T.S.: Did Bogusz take an interest in the fate of the Gallery, and did he review your exhibitions?

Wernisaż wystawy Wandy Wójcik, 1977

Preview of the exhibition by wanda Wójcik, 1977

<

>

T.S.: Did Bogusz take an interest in the fate of the Gallery, and did he review your exhibitions?

T.P.: At that time Bogusz was engrossed in his multiple monumental projects of spatial objects, frequently these concepts were on the verge of utopia. As a rule, he did not attend previous, but he definitely watched exhibitions, and when we occasionally met, he observed “the exhibition was ok”. I did not get an impression that this was just a polite comment; he was not a hypocrite. He even recommended to me Elmar Flammer, a German graphic artist and his friend, and asked me to organize the exhibition by him at the Gallery. I granted his request, since the graphic works were quite interesting, what is more, with no additional costs, I had an opportunity to mount yet another exhibition by a foreign artist which added some variety to the program.

T.S.: Did it happen that you followed similar suggestions made by others whom you considered an authority?

T.P.: Yes, it was obvious that a group of fellow artists talked about art, and newly appearing names. One cannot have a full grasp of what was worth showing. It happened that someone came up with an idea; sometimes it was a good one, sometimes – a washout. I keep in mind one example of a good idea because it came from the person I highly respected: namely Father Jerzy Wolf, an excellent painter and an outstanding connoisseur of art, an author of beautifully written books on the 19th and 20th century Polish painting. He approached me with a timid question, if there was a chance to put up an exhibition by someone who really deserved it but did not know how to arrange a show. His protégée turned out to be Bolek Gasiński, truly a not go-getting type of person. On top of that, hardly one knew that he was painting, and what is more, painting quite well; the exhibition came as a nice surprise for all.

T.S.: Let us talk about exhibitions by foreign artists. There were a few of them, including two from Japan. How did you manage to bring to Warsaw young Japanese artists?

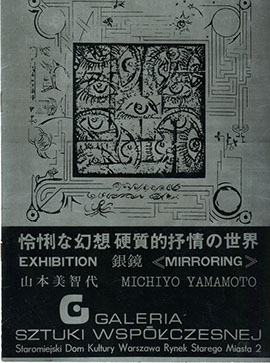

T.P.: I do not take a full merit for this. Rira Inoue, a painter, and Michivo Yamamoto, a graphic artist, were invited – if I remember correctly, under cultural exchange between Poland and Japan – to take part in a plein-air workshop in Białowieża which I happened to attend.

I met them there in the autumn of 1974. Their trip to Poland started in a quite dramatic way. They flew by plane from Tokyo to Warsaw, they were picked up by car from the Warsaw airport and driven to Białowieża Forest, an enclave of the purest air in Europe. Shortly after they arrived, they got very sick. And finally, the diagnose was made - a climatic shock due to an excess amount of oxygen in air – the then Tokyo was one of the most polluted cities in the world. Their bodies had to accommodate to new conditions. I got friendly with the Japanese ladies during the plein-air workshop. When they learnt that I ran the Gallery, they confessed that it was their dream to put up an exhibition in Poland. It happened that I had an opening in the 1975 exhibition agenda, so I booked it for Rira who painted a number of pictures in the course of the workshop. Her painting style was strongly Europe oriented, nevertheless it maintained a certain feature inherent to the Japanese art. The case of Michivo Yamamoto was quite similar. She had her atelier in Japan (she pursued serigraphy). She had to go back home to prepare the exhibition. On top of that, she published a catalogue at her own expense and sent it to Poland. The exhibition took place in 1977 and it met with considerable interest, particularly among graphic artists because serigraphy was a relatively new technique, hardly popularized in Poland. Further, the catalogue was highly impressive; it caused here something similar to a reaction of local African tribes to trinkets brought in by European merchants. I should mention other exhibitions by foreign artists. Jana Ivićiova from Slovakia (or Czech) presented beautiful tapestries in art protis technique. We showed the oeuvre by Juraj Bartusz, a Slovak sculptor. Claudio Capelli, a young Italian painter, landed at the Gallery, recommended by the party apparatus. He gained their support because someone in his family was a high ranking official of the Italian communist party. Fortunately, it turned out that besides proper social background, he boasted an outstanding painting talent.

T.S.: I remember that you had been strongly involved in the Gallery, and suddenly you decided to give up what you approached as the task or even mission to be accomplished. Were there any definite reasons for this decision?

T.P.: I do not think so. Possibly something burnt out… I just wanted to spend more time at my easel. I believe this was they key reason.

T.S.: Thank you very much that in spite of your general reluctance for interviews you agreed to talk to me on the 60th anniversary of the Bent Circle Gallery foundation. And half a century after the Contemporary Art Gallery came into being. This whole half a century has been overshadowed by the legend of the first ten years. I hope that your memories - of an eye witness and co-participant in the Gallery history and its continuation - will contribute to better understanding of this very history.

Teresa Sowińska

Art historian. She worked for the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw in the period 1966-2001.

T.P.: Tak, to było oczywiste, że w gronie kolegów artystów rozmawiało się na temat sztuki, pojawiających się nowych nazwisk. Nie sposób mieć pełną wiedzę o wszystkim, co warte byłoby pokazania. Zdarzało się, że ktoś podsuwał jakiś pomysł, niekiedy dobry, czasem – niewypał. Utkwił mi w pamięci jeden taki pomysłu dobrego przypadek, ze względu na osobę, którą darzyłam wielkim autorytetem; tą osobą był ksiądz Jerzy Wolf, świetny malarz i znakomity znawca sztuki, autor pięknie pisanych książek o malarstwie polskim XIX i XX wieku. Zwrócił się do mnie z nieśmiałym pytaniem, czy istnieje możliwość zrobienia wystawy komuś, kto na to zasługuje, ale sam nie bardzo potrafi zadbać o takie sprawy. Jego protegowanym okazał się znany mi Bolek Gasiński, istotnie mało przebojowy, w dodatku nikt prawie nie wiedział, że on w ogóle maluje, i to nieźle; wystawa była przyjemnym zaskoczeniem dla wszystkich.

T.S.: Porozmawiajmy jeszcze o wystawach artystów zagranicznych, przecież było ich kilka, w tym dwie z Japonii. Jakim sposobem sprowadziłaś do Warszawy młode artystki z Japonii?

T.P.: To niezupełnie ja. Rira Inoue, malarka i Michivo Yamamoto, graficzka, były zaproszone, chyba w ramach wymiany kulturalnej pomiędzy Polską i Japonią, na Plener Białowieski, w którym ja również brałam udział i tam je poznałam, jesienią 1974 roku. Ich pobyt w Polsce rozpoczął się dość dramatycznie. Leciały samolotem z Tokio do Warszawy, tu zostały odebrane z lotniska i samochodem zawiezione do Puszczy Białowieskiej, enklawy najczystszego powietrza w Europie. Wkrótce po podróży bardzo źle się poczuły, okazało się, że to szok klimatyczny, zaszkodził im nadmiar tlenu w powietrzu – Tokio było bodaj najbardziej zanieczyszczonym miastem na świecie – i organizm musiał się przystosować do zmienionych warunków. Zaprzyjaźniłam się z Japonkami podczas Pleneru, a gdy dowiedziały się, że prowadzę Galerię, wyznały, że ich marzeniem jest mieć wystawę w Polsce. Miałam akurat wolne okienko w planie wystaw na 1975 rok, więc zarezerwowałam je dla Riry, która namalowała sporo obrazów na plenerze. Jej malarstwo było mocno zeuropeizowane, ale zachowało pewien rys właściwy sztuce japońskiej. Podobnie było z twórczością Michivo Yamamoto. Ona miała swój warsztat graficzny w Japonii (uprawiała serigrafię) i musiała tam wrócić, by przygotować wystawę. Mało tego, własnym sumptem wydała katalog i przysłała do Polski. Wystawa odbyła się w 1977 roku i wzbudzała duże zainteresowanie, szczególnie wśród grafików, ponieważ serigrafia była dość nową techniką, u nas jeszcze mało spopularyzowaną. Wrażenie robił także katalog; w zbliżony sposób musiały reagować tubylcze plemiona w Afryce na przywożone przez europejskich kupców błyskotki. Powinnam jeszcze wspomnieć o pozostałych wystawach twórców zagranicznych. Jana Ivićiowa ze Słowacji (a może z Czech) pokazała wyjątkowej urody tkaniny wykonane techniką art protis. Była jeszcze wystawa słowackiego rzeźbiarza Juraja Bartusza. Trafił też do Galerii młody włoski malarz Claudio Capelli, skierowany przez jakieś czynniki partyjne, których poparcie zawdzięczał temu, że ktoś z jego bliskiej rodziny był wysokiej rangi działaczem włoskiej partii komunistycznej; na szczęście okazało się, że ma nie tylko dobre pochodzenie, ale i wybitny talent malarski.

T.S.: Pamiętam, że byłaś bardzo zaangażowana w sprawy Galerii, i znienacka postanawiasz zrezygnować z działań, które traktowałaś jako zadanie czy misję. Były jakieś konkretne powody takiej decyzji?

T.P.: Raczej nie. Może coś się wypaliło… Chciałam więcej czasu spędzać przy sztalugach. Myślę, że to był kluczowy powód.

T.S.: Dziękuję Ci, że mimo swojej niechęci do udzielania wywiadów zgodziłaś się na tę rozmowę, w sześćdziesiąt lat po powstaniu Galerii Krzywe Koło. I w półwiecze powstania Galerii Sztuki Współczesnej. To całe półwiecze pozostaje w cieniu legendy pierwszej dekady. Mam nadzieję, że Twoje wspomnienia z pozycji świadka i współuczestnika historii Galerii i jej ciągu dalszego przyczynią się do lepszego tej historii poznania.

Teresa Sowińska

Historyk sztuki, pracowała w Galerii Zachęta w Warszawie w latach 1966-2001.